This collage includes images central to the success of K-pop such as different idols, Internet resources like YouTube, top talent agencies like JYP entertainment, and architectural landmarks from South Korea. Collage is courtesy of http://www.korea-marketing.com

Korean popular music, or K-pop, is an essential component of South Korean tourism. It has become an effective and profitable method to attract tourists because of the endorsement and aid of the South Korean government, the Internet, and the utilization of Idols in campaigns. However, recent events suggest that K-pop tourism will flat line if the government cannot resolve diplomatic issues with the North. Additionally, K-pop idols should specifically tailor their image to appeal to Western ideals in order to harbor growth in European and American tourist markets.

The South Korean government has played a central role in the production and marketing of K-pop since the beginning of the Korean Wave. After the ‘national humiliation’ of the 1997 IMF crisis, one of the government’s main strategies to regain economic power included, “the need to identify and exploit new markets for its products and also diversify the range of products exported” (Dixon). The culture industry was specifically targeted as the government mandated an aggressive international promotion of K-pop (ibid). On the other hand, it took the government much longer to grasp the importance of international tourism.

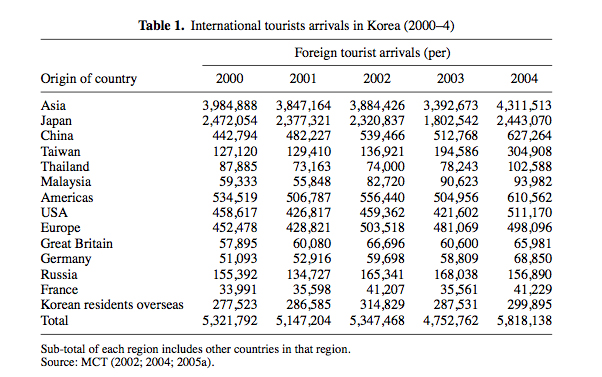

Statistics show that the development of tourism in Korea began after the Korean War (S. Kim et al.). The first inbound tourism figures were produced in 1962 and recorded 15,184 visitors (ibid). In the same year, the government established what is now referred to as the Korean Tourism Organization, or KTO. Some scholars argue that South Korea was viewed as an unfavorable tourist destination because of student riots and perceptions of political instability, specifically, “the images of Korea typically portrayed in overseas news media reports are those of ongoing tensions between South and North Korea and the latter state’s possession of nuclear weapons” (ibid). This all changed after the 1988 Seoul Olympics, which allowed a large global audience to see Korea differently.

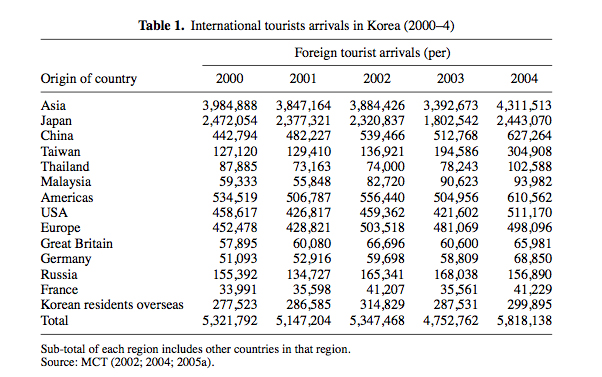

Korean tourism saw a significant growth in 1988, with more than 2.3 million foreign tourist arrivals and foreign tourism receipts that exceeded $3.2 billion (ibid). However, the government did not fully recognize the importance of tourism until after further economic growth following co-hosting the 2002 soccer World Cup with Japan (ibid). For that year the country recorded 5,347,468 visitors and $5.9 billion spending (ibid). The graph below displays the steady increase of tourist arrivals from all over the world between 2000-2004.

Fast-forward to 2011, where it was estimated that the Korean Wave contributed more than $3 billion alone to the South Korean economy (Cox). Despite a shortage of nearly 26,500 rooms in Seoul during the summer of 2010, the government is still aiming to attract more tourists. In an effort to harness K-Pop for tourism, the KTO paid SM Entertainment, one of the country’s largest entertainment companies, approximately $264,000 to stage a concert in France in 2011 (Frances Cha, Harnessing K-Pop for tourism). According to a KTO survey of 3,775 K-pop fans in France, 9 out of 10 said they wished to visit Korea, while more than 75 percent answered that they were actually planning to go (ibid). Because K-Pop draws a lot of foreign tourists to Korea, the South Korean Ministry of Culture and Tourism is developing a multi-functional theme park that will include a K-Pop Town, a K-pop concert hall, and a Hallyu Star Street. The entire project will be completed by 2022.

The future of South Korean tourism will still depend on the actions of the government especially in overcoming historical challenges. During the last quarter of 2012, Japanese tourism to South Korea saw a sharp decrease because of war threats from North Korea. A strong tourism industry is directly proportional to a strong economy, making it crucial that South Korea resolve diplomatic matters quickly to ensure the least amount of damage. The tensions with the North prompted the government to question: how can Seoul be promoted as a safe destination in the foreign media? (Frances Cha, Don’t be afraid, Seoul’s message to tourists). Similar to the situation prior to the 1988 Olympics, North Korea expert Andrei Lankov says, “the problem is that the foreign media believes North Korea’s threats when they should not” (ibid.) Lankov advised the government to flood the media with images that contradict this notion such as ones that display, “…how the day to day lives of South Koreans have remained unaffected by North Korean threats, and how its residents remain unconcerned by the hostile rhetoric” (ibid.) Lankov’s suggestion demonstrates the weight and power the public’s perception has on a country’s tourism industry.

Along with the influence of the government, the Internet and social networking services (SNS) play a significant role in the growth of South Korea tourism. Bored during Christmas break, Kayla Ann Villanueva browsed the Internet looking for an episode of a new show. Without realizing it she clicked on a link to an Asian drama. Soon she finished the season and wanted more. She searched for the names of actors, songs from the series, and for another entertaining show. Villanueva said, “Before I knew it, my computer was full of SHINee songs and my walls were covered in SS501 posters. With my new interest in Korean culture came a desire to learn the language, and with my fervent fascination with Korean pop music came a longing to attend concerts and go to the popular music shows I could only see through my computer screen” (Villanueva).

“It’s the gateway drug,” laughs Lavinia Pletosu, a 22-year-old from Italy. “The more you get into the music, the more you want to know about the language, the history, the culture, the food …”(Cox).

Canadian Mary Zhang agrees: “When I was 15, I wanted to learn Korean so I could write to singer Kim Junsu: he’s a total god. After years of listening to K-pop and practicing the moves, though, I wanted to come and learn about the country” (ibid).

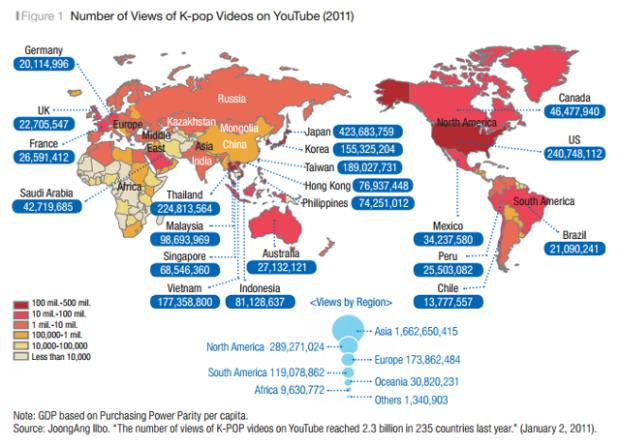

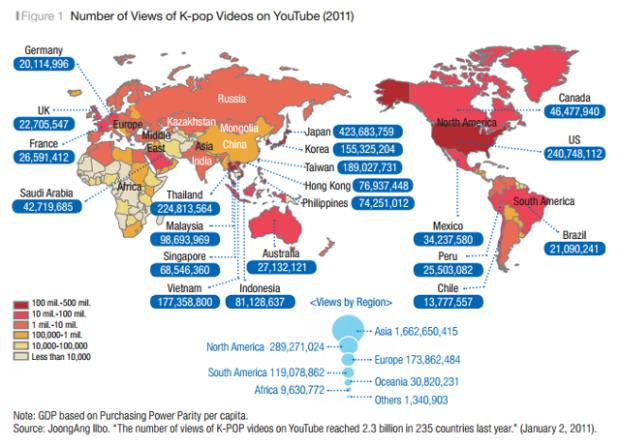

Capitalizing on an opportunity to maximize the reach of K-Pop, tourism officials have used YouTube to attract fans like Kayla Ann Villanueva. The graph below depicts the explosive online popularity K-Pop experienced in 2011. During the year, views for K-Pop videos reached 2.3 billion in 235 different countries (Min-Soo).

In 2012 when PSY’s Gangnam Style became YouTube’s most viewed video of all time, tourism officials posted a guide to the real Gangnam in an effort to ensure that current interest lasted longer than a one-hit wonder. As of December 2012, the video had received more than 400,000 views (Cox). Taking it a step further, in February 2013 YouTube launched the “A-pop channel” which features a top 20 list of the most popular video clips that highlight pop idols in Korea, Japan and China, as well as a calendar that posts information for online fan meetings and events, according to the YouTube’s Korea blog. Users can also view the top 20 list by country, K-pop, J-pop and C-pop, as well as visit featured channels run by top talent agencies such as Korea’s S.M. Entertainment and Japan’s Avex (YouTube launches Asian-pop channel, www.koreaherald.com).

In addition to YouTube, online fan clubs and agency/tourism organization websites also depend on Twitter, Facebook and other SNS in promoting K-pop. Yeon-soo Chung, Executive Director of the Overseas Marketing Department of KTO pays special attention to SNS in regards to a marketing strategy for Chinese tourists. He says, “Bearing in mind that the influence of social networking services (SNS) is growing in China and about 70 % of the total foreign students in Korea are Chinese, we launched a SNS reporters group staffed by Chinese students studying in Korean in a bid to effectively deliver tourism promotional messages to prospective Chinese tourists” (Sung-Mi). These online resources deliver promising results in the expansion of K-pop’s reach and are essential to the heavy marketing of Idol campaigns.

Tourism campaigns that feature K-Pop Idols are not only extremely popular, but they are also the most practical way to connect K-Pop and tourism. The method is successful because it garners participation from fans that are not in geographic proximity to South Korea. For example, KTO’s 2012 global campaign, “Touch Korea Tour Campaign,” advertised the chance for 15 lucky fans to win an all expenses paid trip to Korea during which the winners would meet the goodwill ambassadors and embark on a “mission” together (Frances Cha, Harnessing K-Pop for tourism, www.spotlighttm.com). With Miss A and 2PM as the goodwill ambassadors, the campaign drew participation from 1 million foreigners across the globe (Sung-Mi). Similarly, to celebrate the launch of MTV K in 2013, the network sponsored a “Fly to the Stars Contest” in which contestants had to “Like” the MTV K Facebook page and upload a video explaining why they deserved to meet their idols. Votes will determine the winner who will then receive an all expenses paid trip to Korea to meet their favorite idol.

In promoting these idol tourism campaigns, tourism officials rely on online buzz. “We hope fans of K-Pop around the world will promote this campaign via SNS such as Facebook and YouTube, and offer an opportunity for them to visit Korea and experience it for themselves,” said Shin Pyung-sup, a representative for the tourism brand product team at KTO (Frances Cha, Harnessing K-Pop for tourism, www.spotlighttm.com). But what about people like Kayla Ann Villanueva who stumbled upon K-pop? Although the popularity of K-pop is spreading across Europe and the United States, the number of tourists from each respective region is lower than regional tourists from Asia. Rather than wait for someone to come across the plethora of Internet resources, it is best that the industry develops a specific marketing strategy to engage Westerners in the world of K-pop. In developing this strategy, special attention should be paid to the success of PSY.

Despite previous attempts by Rain and other Idols, PSY was the first K-pop artist to become a viral sensation. The failure of Rain was attributed to his ‘Asianness’. Shin Hyunjoon analyzes, “the ‘Asianness’ was never a merit to appeal to a non-Asian audience. What was a ‘sensitive and delicate’ aesthetic of the Asian artist, sounded ‘soft and dewy’ to the ears of the American music critic. Thus, it was more than ‘language barriers’ that led to Rain’s temporary setback” (Hyunjoon). Based on this analysis, PSY was able to achieve an unmatched level of recognition because he is not the traditional K-Pop idol. BBC reporter Lucy Williamson said PSY was unpolished and unpredictable, but also the most powerful star in Korea topping UK and US music charts. The ‘PSY effect’ is crucial for the development of K-pop tourism because it suggests that traditional idols and idol groups like Girls’ Generation must adopt a different style and image to garner significant attention in the United States and Europe.

To conclude, K-pop has become an effective and profitable method to attract tourists because of the endorsement and aid of the South Korean government, the Internet, and the utilization of Idols in campaigns. However, recent events suggest that K-pop tourism will flat line if the government cannot resolve diplomatic issues with the North. Additionally, K-pop should abandon the traditional idol system in order to appeal more to potential Western tourist markets.

The South Korean government has played a central role in the production and marketing of K-pop since the beginning of the Korean Wave. Recognizing the importance of tourism after further economic growth following co-hosting the 2002 soccer World Cup with Japan, the South Korean government promoted K-pop as a cultural export. In 2011, the Korean Wave contributed more than $3 billion alone to the South Korean economy, and many foreigners cite K-pop as their reason for traveling to South Korea. But this well-oiled machine has recently shown signs of struggle. According to data from the last quarter of 2012, Japanese tourism to South Korea saw a sharp decrease because of war threats from North Korea. Above all else, the government’s direct responsibility in ensuring the growth of K-pop tourism is to resolve diplomatic tensions as quickly as possible.

Internet and social networking services (SNS) play a significant role in the growth of South Korea tourism. Capitalizing on an opportunity to maximize the reach of K-Pop, tourism officials have used YouTube to attract fans like Kayla Ann Villanueva. During the year, views for K-Pop videos reached 2.3 billion in 235 different countries. In addition to YouTube, online fan clubs and agency/tourism organization websites also depend on Twitter, Facebook and other SNS in promoting K-pop.

These tools are used to help market Idol tourism campaigns such as KTO’s 2012 global campaign, “Touch Korea Tour Campaign,” which advertised the chance for 15 lucky fans to win an all expenses paid trip to Korea during which the winners would meet the goodwill ambassadors and embark on a “mission” together.

Although the popularity of K-pop is spreading across Europe and the United States, the number of tourists from each region is lower than regional tourists from Asia. Rather than wait for someone to come across the plethora of Internet resources, it is best that the industry develops a specific marketing strategy to engage Westerners in the world of K-pop. In doing so, special attention should be paid to PSY’s unconventional image in correlation with his viral success.

In order for K-pop Tourism to sustain itself and transcend time and place, it must be able to overcome cultural, political, and technical obstacles.

Bibliography:

Cha, Frances.”Don’t be afraid, Seoul’s message to tourists.” CNN Travel. 9 April 2013. Accessed 24, April 2013. <http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/08/travel/south-korea-tourism>

Cha, Frances. “Harnessing K-Pop for tourism.” Spotlight. 17 April, 2013. Accessed 24, April 2013. < http://www.spotlighttm.com/groups/world-country-groups/viewbulletin/287-harnessing-k-pop-for-tourism?groupid=174>

Cox, Jennifer. “Seoul searching: on the trail of the K-pop phenomenon.” The Guardian. 28 Dec 2012. Accessed 24, April 2013. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/travel/2012/dec/28/seoul-k-pop-gangnam-style>

Dixon, Tom. “The Journey of Cultural Globalization in Korean Pop Music.” E-International Relations, 17 Aug, 2011. Accessed 24, April 2013. < http://www.e-ir.info/2011/08/17/the-journey-of-cultural-globalization-in-korean-pop-music/>

“E-Land Named Developer of Jeju Theme Park.” Visit Korea. 20 March 2013. Accessed 24 April 2013. <http://english.visitkorea.or.kr/enu/bs/tour_investment_support/pds/content/cms_view_1806113.jsp>

Kim, Sangkyun; Long, Philip; Robinson Mike. (2009): Small Screen, Big Tourism: The Role of Popular Korean Television Dramas in South Korean Tourism, Tourism Geographies: An International Journal of Tourism Space, Place and Environment, 11:3, 308-333

Min-Soo, Seo. “Lessons from K-pop’s Global Success.” Korea Marketing. Accessed 24 April 2013. < http://www.korea-marketing.com/lessons-from-k-pops-global-success/>

Sung-Mi, Kim. “Foreign tourists visiting Korea poised to hit 10 million mark.” IT Times. 10 July 2012. Accessed 24 April 2013. <http://www.koreaittimes.com/story/22243/foreign-tourists-visiting-korea-poised-hit-10-million-mark>

Villanueva, Kayla Ann. “Kayla Ann Villanueva: I moved to Korea for K-Pop.” CNN Travel. 12 Jan 2012. Accessed 24 April 2013. <http://travel.cnn.com/seoul/visit/tell-me-about-it/kayla-ann-villanueva-k-pop-was-why-i-moved-korea-925216>

“YouTube launches Asian-pop channel.” The Korea Herald. 19 Feb 2013. Accessed 24 April 2013. http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20130219000974

This work by Meredith Browne is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.